A product is a good, service or idea that caters to (of fulfills) the needs and desires of organizations, social groups or individuals. A brand is a diverse collection of thoughts, emotions and opinions that are channeled into conscious as well as subconscious expectations of the product.

Products can be described intellectually and compared rationally. The brand, however, comprises a whole range of mental associations which, by their nature, are much harder both to describe and to compare.

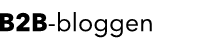

I like to simplify this argument by dividing each offering into three parts:

- Function/Performance

- Value/Benefit

- Relationship/Trust

When I lecture salespeople, I often say that they prefer to focus their sales arguments on function, performance and price (the latter is the most basic part of Value/Benefit). Unfortunately, the same argument can be applied to how many brands communicate.

The dilemma is that that which makes the buyer want to buy, and spurs her to arrive at the decision to do so, is almost exclusively the benefits she believes she will gain and how she experiences her relationship with, and confidence in, the seller (and/or the brand). Science has in fact confirmed that basically all decisions – big and small, in B2B as well as in B2C – are based on emotional factors, not rational. We choose with our hearts, but justify with our brains, the proof of which brought Daniel Kahneman the Nobel Prize.

In addition, the salesperson – by focusing on function, performance and price – lays him or herself open to what I call intellectual competition, because the offering can be easily compared to any competitor’s. When that happens, there is always at least one other company which can surpass the salesperson’s offering on at least one point.

On top of that, since the offering can be measured, weighed and valued intellectually, the slightest mistake in delivery, performance or service is cause for the buyer to experience disappointment. Confidence is damaged. The relationship is weakened. The perceived value is reduced. And this also reduces the buyer’s willingness to pay the price (or incentive to buy again).

Mark Michalek is probably one of the world’s best car salesman ever. For a long period of time he averaged an amazing 37 car sales per month, against an average of maybe 10-15, and his record is 13 cars sold to retail customers in one day(!). He was once asked what he does that others do not, and replied that the secret is in his motto:

“Make a friend, sell a car, make money.”

What Mark Michalek intuitively understood, and managed to achieve in practice, is that people buy from people they like and trust. Mark does not sell cars by focusing on function, performance and price, but by focusing on (and answering) the buyer’s needs and desires, and by building and maintaining a strong relationship with each of his approximately 3 500 customers.

The same applies to brand building. Companies that focus on the customer-perceived benefits of their offering, and then build strong customer relationships, apply what I call emotional competition. This makes it much more difficult for other brands to offer an alternative that the buyer actually feels is ‘better’, because ‘better’ is a complex and subjective decision which, in most cases, is won by the brand the buyer likes most. This preference also makes the buyer considerably more tolerant of any errors or omissions in the product, because we always find it easier to forgive those we like. It’s a watertight strategy, because the purchase is not based on rational, measurable considerations (the product itself) but on emotional and un-measurable considerations – the perceived usefulness of the product and the buyer’s relationship with and confidence in the brand.

Function, performance and price are not irrelevant. A strong brand is most often anchored in a good product. However, the importance of function, performance and price is secondary – not least in all those industries where differences between different products’ actual performance (and price) are so arbitrary that the buyer does not perceive them as being relevant.

In short: distinguish the difference between product and brand. Between what it is and what it does.

And please don’t put all your effort into communicating what the buyer already takes for granted – that the product is what it is, and that it costs money to buy.

This post was originally published in Swedish on Micco Grönholm’s blog The Brand-Man.